When Power Dresses as Order: The Aesthetics of Control

Authoritarianism and Corporate Dystopia in History, Literature, and Cinema

Introduction

Authoritarianism rarely arrives wearing a uniform.

More often, it comes quietly wrapped in the language of efficiency, security, productivity, and progress. It presents itself as reasonable. Necessary. Inevitable. Over time, control stops looking like oppression and starts feeling like normality.

History has seen it.

Literature has warned us about it.

Cinema has visualized it long before we recognized it in ourselves.

From rigid bureaucracies to corporate hierarchies, from propaganda posters to brand guidelines, the aesthetics of power have evolved, but their purpose has remained strikingly consistent: to simplify human complexity into something manageable, measurable, and compliant.

This article is a journey through those warnings.

Not as a lecture.

Not as nostalgia.

But as a reflection.

Across centuries, writers, filmmakers, and artists have imagined futures in which freedom wasn’t taken by force but traded for comfort, stability, convenience, or distraction. Those imagined worlds now feel uncomfortably familiar.

Today, the mechanisms of control are often cleaner, softer, more abstract:

dashboards instead of batons

metrics instead of mandates

branding instead of banners

This is where corporate dystopia emerges not as science fiction, but as atmosphere.

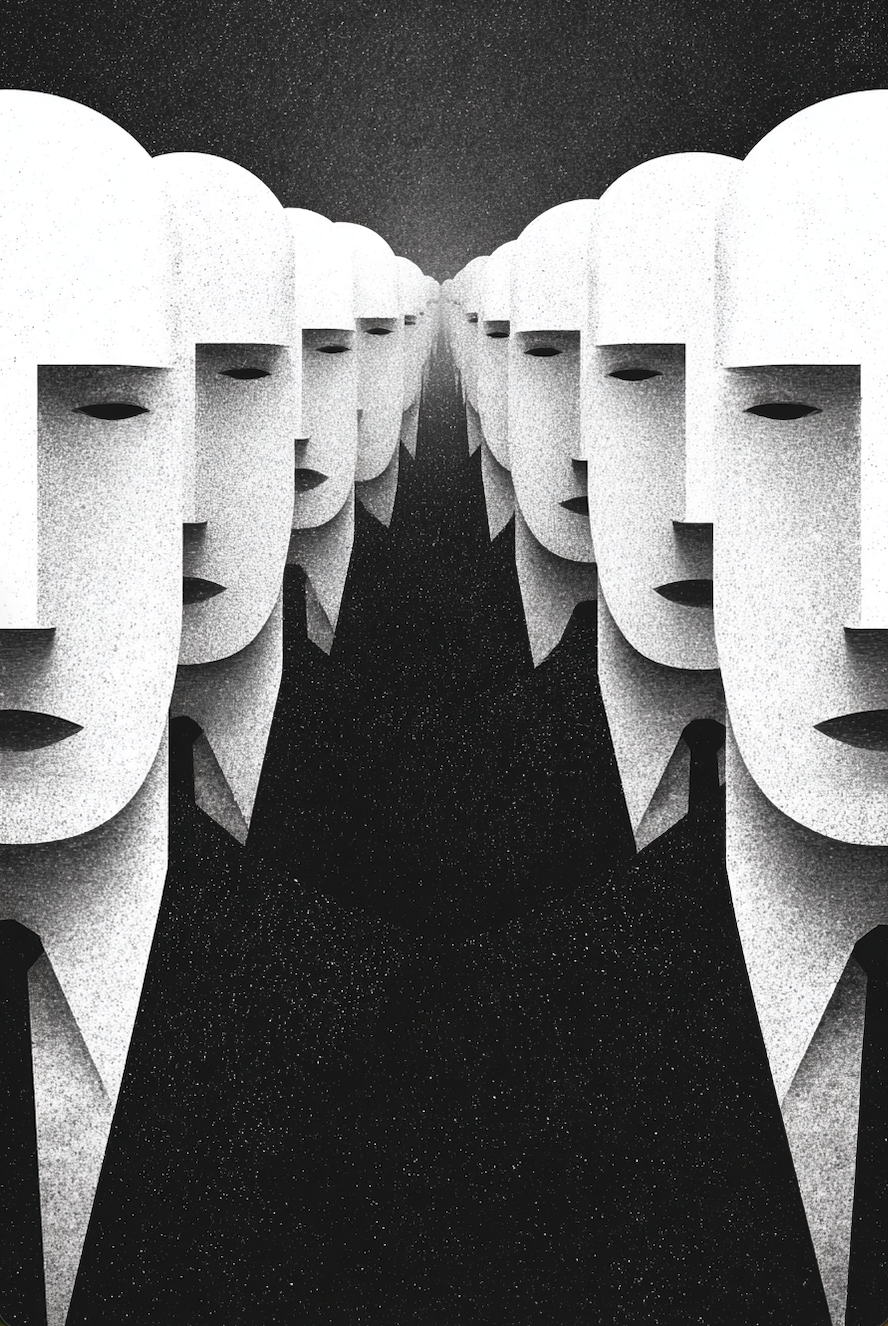

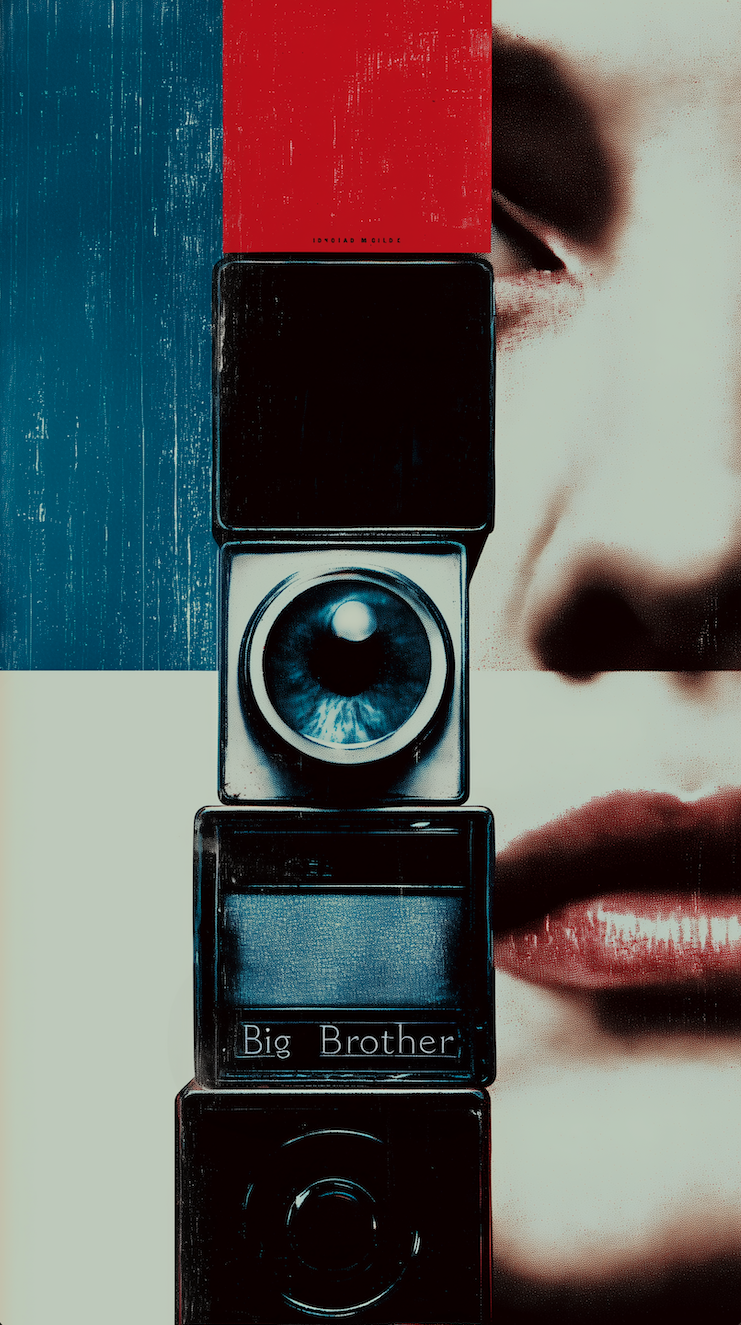

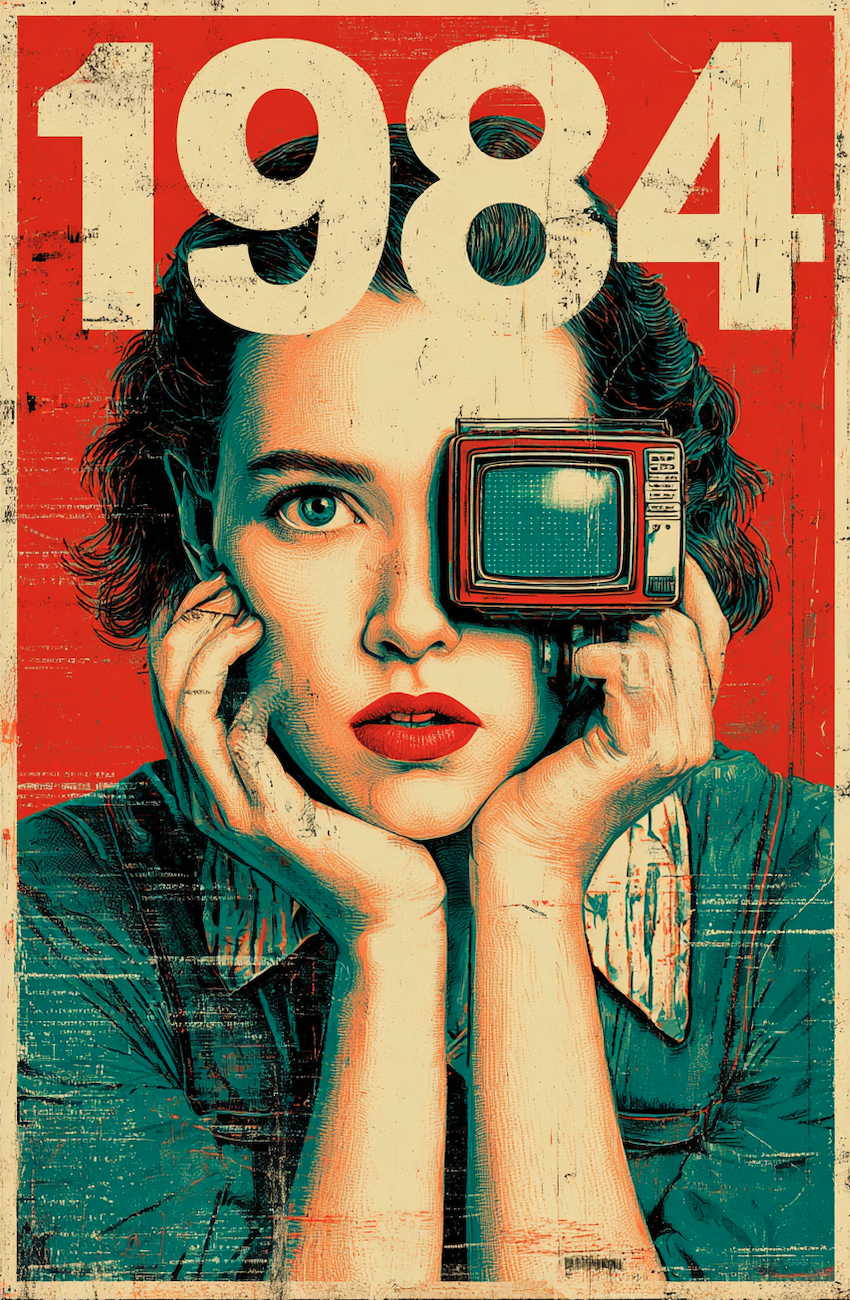

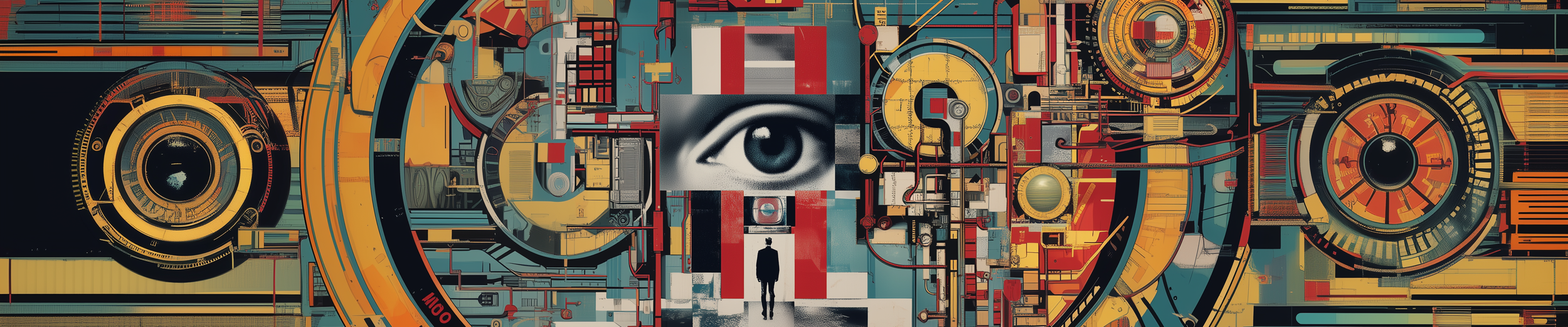

The images accompanying this essay are not illustrations of the past. They are visual echoes, minimal, symbolic interpretations of recurring patterns: surveillance, conformity, hierarchy, and sanitized language. They are meant to pause the reader, not instruct them. To raise questions, not provide answers.

Along the way, we’ll revisit key works of literature and cinema that shaped our collective understanding of authoritarian systems, stories that didn’t predict the future as much as reveal human tendencies. These works remain relevant not because they were right about technology, but because they were right about us.

This is an invitation to look again.

In history.

In the culture.

At the walls we decorate, the words we accept, and the systems we participate in.

And to ask, quietly but honestly:

At what point does order become obedience?

I. The Historical Roots of Control

When Authority Learns to Look Reasonable

Authoritarianism does not begin with cruelty.

It begins with order.

Historically, systems of control have always justified themselves as solutions to chaos: economic instability, social unrest, moral decay, and external threats. The promise is simple and deeply human: safety in exchange for obedience. Over time, this trade becomes normalized, even welcomed.

Early authoritarian regimes relied on visibility: uniforms, banners, parades, and monuments. Power needed to be seen to be believed. Architecture grew imposing. Language became absolute. Citizens were reminded daily, physically and symbolically, of who was in charge.

But something subtler happened as these systems matured.

Control shifted from spectacle to structure.

Bureaucracy replaced brute force. Rules replaced violence. Paperwork replaced punishment. The most effective systems did not require constant enforcement; they trained people to enforce themselves. Once compliance becomes routine, resistance begins to feel disruptive, irrational, even dangerous.

This is the critical historical pivot:

When authority stops appearing as domination and starts presenting itself as administration.

In these systems:

Responsibility dissolves into procedure

Moral decisions are outsourced to policy

Harm becomes an unintended “side effect.”

No single individual feels accountable—because everyone is “just doing their job.”

Visual culture followed this evolution. Propaganda became cleaner. Messaging became abstract. Symbols replaced slogans. The emotional temperature cooled. What remained was a sense of inevitability: this is how things are done.

These historical patterns matter because they reveal something uncomfortable: authoritarianism does not survive on fear alone. It survives on participation. On the quiet agreement of millions who believe they are being reasonable.

The past shows us this clearly—not as a distant horror, but as a recurring human tendency. Systems grow. Structures harden. Language softens. And control learns to wear the mask of normality.

This is the soil from which dystopian literature and cinema would later grow—not as fantasy, but as recognition.

| Once power learned to hide behind structure, storytellers began to notice—and to warn us.

II. Literature as an Early Warning System

Stories That Didn’t Predict the Future. They Recognized Us

Long before algorithms, dashboards, and corporate mission statements, writers understood something essential: systems of control don’t begin with violence — they begin with agreement.

Dystopian literature was never about predicting technology. It was about exposing human behavior under pressure: our desire for comfort, our fear of uncertainty, and our willingness to trade freedom for reassurance. These stories endure because they are not warnings about what might happen, but mirrors held up to what already was.

Surveillance, Language, and Internalized Control

Orwell’s world is often reduced to cameras and telescreens, but its most disturbing insight is psychological. Power does not rely solely on observation; it relies on self-regulation. Citizens learn to censor their thoughts, adjust their memories, and mistrust their own perceptions.

Language itself becomes a weapon. By shrinking vocabulary, the system shrinks the range of possible thoughts. Control succeeds not when dissent is punished, but when it becomes unthinkable.

If there is one book that still resonates in an age of data collection, behavioral tracking, and algorithmic visibility, this is it, not because it predicted modern tools, but because it understood modern compliance.

(Recommended for readers interested in surveillance culture, media control, and the psychology of obedience.)

Comfort as Control

Where Orwell imagined oppression through fear, Huxley imagined something more seductive: control through pleasure.

In this world, citizens are entertained, medicated, and distracted into compliance. There is no need for force because discomfort itself has been engineered out of existence. Freedom becomes irrelevant when no one feels the desire to question.

This vision feels uncannily modern. Endless content. Engineered happiness. Consumption as identity. Corporate stability is presented as a moral good.

For readers trying to understand why dystopia today often feels comfortable, polished, and branded, this book remains essential.

(Recommended for those exploring consumer culture, corporate power, and the illusion of choice.)

When Thinking Becomes Dangerous

Bradbury’s world does not ban books because they are powerful. It burns them because they are inconvenient. Complex ideas disrupt the smooth functioning of society. Reflection slows consumption. Silence invites thought.

What makes this story enduring is its focus on anti-intellectualism, a culture that willingly abandons depth for speed, nuance for slogans. Authority doesn’t need to impose ignorance when people choose it themselves.

In an era of shrinking attention spans and algorithmically optimized content, this warning feels less like fiction and more like documentation.

(I recommend it for readers concerned with media saturation, distraction, and cultural flattening.)

The Blueprint of Modern Dystopia

Often overlooked, We is the quiet foundation upon which much dystopian literature rests.

Here, individuality itself is the threat. Citizens are numbers. Transparency is mandatory. Privacy is pathology. The system does not hide its control; it celebrates it as rational, scientific, and inevitable.

What makes this novel especially relevant today is its emphasis on mathematical order and optimization, a worldview in which efficiency overrides humanity and treats unpredictability as a defect.

For readers interested in the philosophical roots of technocratic and corporate dystopias, this book is indispensable.

(I recommend it for those drawn to systemic thinking, algorithmic governance, and dehumanization by design.)

Why These Books Still Matter

Taken together, these works reveal a shared insight:

The most durable systems of control are those that people defend themselves against.

They do not rely on villains, but on structures.

Not on cruelty, but on normalization.

Not on force, but on participation.

This is why they continue to inspire visual culture, posters, films, and contemporary art that strip power down to its symbols, its language, its clean surfaces. The images that accompany this essay are not illustrations of these books, but conversations with them.

The next step in this evolution would not remain on the page.

It would move to the screen.

| If literature taught us how control feels from the inside, cinema would soon show us how it looks from the outside.

III. Cinema and the Visual Grammar of Authority

When Control Learned How to Look

If literature explored authoritarianism from the inside, cinema gave it form.

Film did not merely present control narratives; it constructed its atmosphere. Architecture, costume, sound, framing, and color became tools of ideology. Power was no longer abstract; it was visible, spatial, and emotional.

Dystopian cinema taught us how authority feels before we could name it.

Metropolis

Hierarchy Made Monumental

One of the earliest and most influential dystopian films, Metropolis presents a world literally divided by elevation. Above ground: light, gardens, leisure. Below: machinery, repetition, exhaustion.

Power here is architectural. Control is embedded in the built environment. Workers move in synchronized patterns, not because they are forced to, but because the system allows no alternative rhythm.

Nearly a century later, this visual language remains intact, echoed in corporate headquarters, financial districts, and glass-and-steel skylines. Cinema didn’t invent these hierarchies; it simply made them impossible to ignore.

Brazil

Bureaucracy as Absurd Violence

Where Metropolis monumentalized power, Brazil suffocated it in paperwork.

This world is not ruled by tyrants, but by forms, stamps, and procedures. The cruelty is accidental, the suffering administrative. No one intends harm; harm simply emerges from a system optimized for itself.

What makes Brazil enduring is its tone. The film is darkly comic, surreal, and almost playful; that is precisely the point. Authoritarianism here is not frightening because it is brutal, but because it is ridiculous and unstoppable.

This vision resonates deeply with corporate dystopia: endless processes, shifting rules, responsibility diluted into systems that no one fully controls.

V for Vendetta

Fear as a Management Tool

In V for Vendetta, authoritarianism returns to the foreground, but in a modernized form.

The regime governs not through constant force, but through narrative control: media repetition, symbolic enemies, and manufactured crises. Surveillance is normalized. Compliance is framed as patriotism. Fear becomes a civic duty.

What makes this film especially relevant today is its understanding of spectacle. Authority is theatrical. Symbols matter more than truth. The order is performed daily until it becomes a ritual.

The mask is not just a disguise; it is a reminder that power survives through symbols long after leaders disappear.

Children of Men

Collapse Through Apathy

Unlike classic dystopias, Children of Men offers no grand ideology. The system hasn’t become cruel; it has simply given up.

Surveillance exists. Militarized borders exist. Camps exist. But no one claims they are good. They are merely necessary. Temporary. Inevitable.

This is perhaps the most unsettling vision of all: authoritarian structures persisting not because people believe in them, but because imagining alternatives feels exhausting.

Visually, the film is grounded, documentary-like, and almost mundane. Control no longer needs to announce itself. It blends into daily life.

The Visual Legacy of Dystopian Cinema

Together, these films established a shared visual grammar:

monumental architecture

repetitive human movement

muted palettes and institutional color schemes

Authority framed as environment, not antagonist

This grammar now extends far beyond cinema, into advertising, interface design, corporate branding, and public space. Dystopia has become aesthetically familiar, even comfortable.

| Once dystopia became familiar on screen, it no longer needed fiction to survive.

IV. Corporate Dystopia

When Control Becomes Design

Corporate dystopia does not announce itself.

It doesn’t arrive with flags or slogans. It comes through interfaces, policies, branding, and processes. It speaks in the language of optimization, alignment, and efficiency. Its authority is not enforced; it is designed.

In this world, control is no longer exercised primarily through fear, but through participation. People are not ordered to comply; they are encouraged to opt in. Metrics replace mandates. Dashboards replace decrees. Performance indicators quietly redefine value, success, and even identity.

What makes corporate dystopia distinct from its historical predecessors is its tone.

It is calm.

Neutral.

Professional.

Power no longer needs to raise its voice.

Language plays a central role. Terms like best practices, roadmaps, deliverables, compliance, and alignment appear harmless, even helpful. Yet they gradually abstract responsibility, flatten nuance, and distance individuals from the consequences of their actions. Decisions are no longer moral; they are procedural.

No one is cruel.

No one is guilty.

Everyone is “just doing their job.”

This is the aesthetic of modern authority: clean typography, neutral color palettes, reassuring slogans. Even dissent is absorbed, rebranded, and sold back as innovation. The system doesn’t suppress critique; it commodifies it.

Surveillance, too, has changed character. It is no longer imposed; it is embedded. Tracking becomes feedback. Observation becomes personalization. Visibility is framed as transparency, and transparency as trust. The result is a culture where people voluntarily document themselves, measure themselves, and optimize themselves, often without being asked.

Corporate dystopia thrives not because people are coerced, but because the system is convenient.

It removes friction.

It reduces uncertainty.

It offers belonging through standardization.

And like all effective systems of control, it slowly reshapes what feels normal.

It is the reason why contemporary dystopia often looks minimalist rather than brutal. Why does authority feel ambient rather than oppressive? Why the most unsettling images are not violent scenes, but empty slogans, perfect grids, and assuring statements that say nothing at all.

The posters, symbols, and visual fragments that make up the Corporate Dystopia collection are born from this realization. They don’t depict tyrants or disasters. They depict atmospheres. They isolate the language, the forms, and the visual habits of power, and hold them still long enough to be seen.

Not to accuse.

Not to instruct.

But to interrupt.

Because the most effective question is often the quietest one:

When did this start to feel normal?